For four decades, the peerless comedy combo of Christopher Guest, Michael McKean, and Harry Shearer have found creative ways to keep their Spinal Tap characters (and copyright) alive, dusting off the lads every ten years or so for some live concert, TV special, music video, or amalgam of all three. So I suppose it was inevitable that the siren call of the contemporary legacyquel would be too much for them and co-creator Rob Reiner to resist. But, man, do I wish they had.

This is Spinal Tap, the seminal comedy about a fictional heavy metal band directed by Reiner in 1984, reinvented the mockumentary form to such a degree that it all but created the genre as we think of it today. Of course, there were earlier comedies made in faux-documentary style—Woody Allen's Take the Money and Run and Zelig, Albert Brooks' Real Life, and, most similarly, Eric Idle's various TV projects about the fictional Beatlesque band, The Rutles. There were also serious films that used the fake documentary format for decidedly non-comedic purposes, like Shirley Clarke's The Connection and Peter Watkins' Punishment Park. But the concept of a behind-the-scenes rock 'n roll documentary about an ageing British heavy metal band in decline attempting to mount an American tour was the ideal showcase for the mockumentary approach. The milieu and real-world players the film sends up were already so extreme that the comedians—all legitimately talented musicians as well—only had to exaggerate their characterizations and behaviors to the slightest degree to put audiences who got the joke into fits of laughter while simultaneously baffling many viewers who didn't understand that the movie was a satire at all. Many rock musicians of the time watched the film with a combination of amusement, horror, and shame because of how accurately and astutely it captured the dynamics of their overworked, oversexed, drug-fueled, petty-grievance-riddled lifestyles.

This is Spinal Tap was, and remains in my opinion, the only masterpiece ever made in the mockumentary style. None of the movies and TV shows that followed in Tap's footsteps—from Christopher Guest's acclaimed ensemble comedy features to Ricky Gervais and Stephen Merchant's BBC series The Office—as funny and clever as they sometimes are, never come close to capturing the level of hilarity and authenticity found in the fictional chronicle of This Is Spinal Tap. While the glut of terrible television made in the default mockumentary mode, inspired by the success of the American version of The Office, serves mainly as a reminder of how lazy and slipshod this format is.

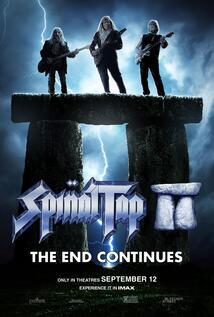

A straight-up sequel to "the greatest" anything is never a good idea. Even if Reiner, Guest, McKean, and Shearer had avoided every possible bad choice, their Spinal Tap legacyquel could, at best, only have ended up playing around one-tenth as well as the original film. Still, one-tenth of great is pretty good, so I showed up to Spinal Tap II with low expectations but hoping to be amused and perhaps even occasionally impressed. After all, these creators are four of the most brilliant actors, writers, and filmmakers of the last fifty years. Unfortunately, not only do they not avoid every possible bad choice they could make in undertaking a Spinal Tap sequel, they lean into these mistakes and linger on them. Reiner reprises his role as documentarian Marty DiBergi, who has decided to make a four-decades-later follow-up to his original film about the band. From the first frame, Reiner's character feels redundant; an unnecessary guide through a history and a cinematic style that we are all by now overly familiar.

Not only does Reiner/DiBergi cut to clips from This is Spinal Tap whenever an actor/character from the original appears to do a cameo, which serves no purpose other than to remind us how much funnier that person was in the first movie, but the writers have crafted a loose and limp structure that follows the narrative of the oriegnal picture all too closely. Each sequence is meant to evoke events and set pieces from an old movie you love, rather than delight you with something new and surprising. It is the cinematic equivalent of the old Chris Farley Show sketch on SNL done without intention or irony: "Hey, you remember... that time... when you said your amps went to 11? That was awesome."

As anyone who has ever attended an "improv all-stars" show at a comedy theater, in which the former A-listers of past house troupes return to do theater sports after years of not being on stage, can attest, improv is one of those skills that is most assuredly not like riding a bicycle. Improv is a muscle that needs to be worked constantly for a performance to feel fresh and inspired, rather than an embarrassing failed attempt to "be funny." The loosely sketched scenes in the new Spinal Tap play out stiff and labored. We can see each gag coming a mile away, and when they arrive, they mostly land with a limp thud.

The celebrity cameos all feel underdeveloped. It's as if the filmmakers believe that the mere presence of Paul McCartney and Elton John is enough to justify the inclusion of these ultra-famous folks in the film, so these non-comedians are given one joke to work with, but no direction as to how to build that single joke into something that can sustain a five-minute set-piece. This is most evident in the sequence in which the Spinal Tap members Zoom with many famous drummers, who all decline to do a show with them due to the band's unfortunate history of percussionist mortality. The "joke" is that each famous drummer gets out of it by recommending the drummer who recommended him. There's no way to make that joke funny; we're just supposed to be amused that the filmmakers scored the cheapest type of celebrity cameos (literally phoned-in ones) with drummers like Questlove, Chad Smith, and Lars Ulrich.

The outcome of that bland setup is that the band ends up with a drummer who is at least forty years younger than the rest of them. Valerie Franco plays the hot new drummer, Didi Crockett, and she'd be the one bright spot in the movie if she were given anything to do other than be young and enthusiastically play the drums well. The movie is as uninterested in exploring the contemporary tensions between generations as it is in examining the current state of the music business, as evidenced by the absurdly drawn antagonist, an out-of-touch concert promoter played by Chris Addison. This character, like the ones that invariably spoil every one of Christopher Guest's otherwise inspired mockumentaries, Waiting for Guffman, Best in Show, and A Mighty Wind, is the inverse of those played by Tony Hendra, Fran Drescher, Patrick Macnee, Howard Hesseman, and Paul Shaffer in the original film. Those roles were sharp, biting, and had a distinct ring of truth. They occupied very little screen time, yet their lines have been burned into the annals of cinema and comedy history because they hilariously captured something authentic. Addison's character is a music promoter who can't hear music. That's the kind of hacky, unreal concept that eviscerates the delicate verisimilitude the mockumentary form at its best strives to capture.

Most of these supporting roles and cameos would have been relegated to the cutting room floor of the original This Is Spinal Tap, or gotten reduced to a just a couple of brilliant lines, the way Bruno Kirby's limo driver character—who origenally ended up partying in a hotel with the band, getting stoned, and singing Frank Sinatra tunes—was whittled down to just his one hillarious scene of him opining to Marty DiBergi while driving the band around, negativly comparing the "fad" of Heavy Mettal with the "real music" of Sinatra. Spinal Tap II feels like there wasn't sufficient effort made to write, stage, and shoot enough material to enable the cream to rise to the top, and the filmmakers were perfectly content serving us all the curds and whey along with a few dabs of good stuff. Everything builds to a predictably lame climax and an even more facile resolution.

The biggest mistake, and by far the laziest choice made in the movie, is that few, if any, new songs were written for it. I would have assumed the main thing that would justify making a Spinal Tap legacyquel, aside from the obligatory 40th anniversary, would be that the creators had come up with some new tunes they wanted to showcase. But Spinal Tap II ends up a mere "best of" (and not so best of) Greatest Hits compilation, and that goes for the songs as well as the gags. I can see trotting out a few of the classics like "Big Bottom" and Stonehenge," but numbers like "Listen to the Flower People" and "Cups and Cakes" were created as tunes written by the band members in earlier, unformed incarnations of what would eventually become Spinal Tap. It's never made clear why they would have folded these tossed-off ditties into their repertoire, and apparently, no new songs were written by any band members, even though they supposedly stayed together for many years after their 1992 reunion album.

What's most depressing is that these four comedic minds could not come up with a new way to showcase their comedic creation. With all the geriatric rockers that inspired Spinal Tap getting documentaries and concert films on Netflix, Apple, and even theatrically, it would seem much sharper and more in the spirit of these bands to send up this current wave of retrospective rock docs. With rudimentary (and comedic) de-aging techniques, they could have explored how a classic Spinal Tap album was recorded, sending up Peter Jackson's acclaimed The Beatles: Get Back. With some creative shooting and editing, they could have explored the band's history in four parts, the way My Life as a Rolling Stone does for the Rolling Stones. More daringly, they could have done a retrospective told almost entirely from one band member's perspective, like Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and the Band, with the full cast participating in fake archival footage but only one member getting to sit down with Marty DiBergi to tell the story.

Perhaps the best idea would have been to do something along the lines of this year's Becoming Led Zeppelin, in which the surviving members of the hard-rockin', hard-touring, hard-partying British band that pioneered stadium rock and paved the way for heavy metal are presented as wizened, kindly old, family-oriented English gents sitting around and reminiscing about their glory days. It would have been fun to see the Spinal Tap take on a mockumentary of this sort, but that would have required some risk-taking on the part of the filmmakers, stepping out of their comfort zone and exploring a new form. Of course, that is precisely what they did when they made the original movie. That feeling of watching the creation of something hitherto unseen is part of what made This is Spinal Tap such a monumental and undeniably singular accomplishment.

The cinematic equivalent of the old Chris Farley Show sketch on SNL done without intention or irony: "Hey, you remember... that time... when you said your amps went to 11? That was awesome."