Writer/director Scott Cooper manages to combine my two least favorite types of movie—boomer biopic and millennial apology porn—and adds the now-fully-coalesced terrible Gen-X filmmaker trope of substituting character development for shots of the protagonist sitting on a sofa watching old movies, drunk or high or depressed. Yet he somehow managed to produce a movie so limp and lame that I couldn't even work up much rage about it. In fact, this picture is so tedious that it marks the first time I've ever nodded off in an IMAX cinema.

In 1996, Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski (the screenwriters of Ed Wood, who have been absurdly overpraised for writing the same terrible biopic script over and over again for 30 years) penned the God-awful but highly acclaimed The People versus Larry Flint. In that film's opening moments, they depict young Larry and his brother in the 1950s back woods where they grew up, selling their father's moonshine behind his back, which causes the drunken dad to chase the boys with a rifle. The flashback is meant to establish Flynt's roots and encapsulate his lifelong predilection for pushing against hypocritical authority. That was back in 1996, and it was the first time I ever registered what a bad biopic cliché was. The rest of the movie would have had to have been phenomenal to win me back (but that movie ain't phenomenal). And, much to my chagrin, the trope persisted, especially in musical biopics.

A decade later, Jake Kasdan and Judd Apatow would mock this worn-out convention in their spoof of musical biopics, Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story, by having young Dewey Cox accidentally slice his brother in half with a machete resulting in his grudge-holding father showing up thoughout the picture to remind Dewey that, in his father's eyes, "the wrong kid died." I thought, surely this will be the nail in the coffin for this trope. Hell, Walk Hard should have forced an entire reassessment of the musical biopic sub-genre. But that just ain't gonna happen in today's IP-obsessed cinematic universe. While there have certainly been some inventive examples of the questionable narrative form since Walk Hard—Love & Mercy, which explored Brian Wilson's struggles with mental illness during two key times in his career, and A Complete Unknown, which captures a transformative era in music by heavily fictionalizing the first five years in Bob Dylan's career, to name the only two that spring to mind. But by and large, most of these movies amount to little more than misleading visual Cliffnotes of a life and opportunities for great actors to win awards for mimicry.

I'll be surprised if anyone wins an award for this movie. Cropper's adaptation of Warren Zanes' well-researched book about the making of Bruce Springsteen's Nebraska album, and the role it played in the iconic rocker's career, literally uses the "the wrong kid died" flashback trope and spreads it on thick. No, Bruce didn't have a dead brother, but he had a drunken, abusive pop who seemed to have left him scarred in ways that haunted him for the first several decades of his life. Starting in Black and White with little boy Bruce trapped between his nurturing but overwhelmed mom (Gaby Hoffmann) and his volatile dad (Stephen Graham), these monochrome memories are a constant in the movie, as are atrociously written scenes in which characters try to explain to each other why Springsteen is so dark and moody.

Cooper takes the iconic Rocker/songwriter's most poetic album and tries to explain it to us in much the same way those uptight, uncreative English teachers in Dead Poets Society encouraged their students to use Dr. J. Evans Pritchard's rating method to evaluate the work of Byron, Whitman, and Shakespeare before Robin Williams bounces in to point out how absured that notion is. The director of Crazy Heart, Out of the Furnace, Black Mass, and The Pale Blue Eye provides some of the most reductive, limited, and downright silly explanations for the inspirations behind the songs Springsteen wrote after the runaway success of The River, the 1980 hit studio album designed to capture the energy of his live band's concerts. After touring to promote that record, Bruce holed up in his bedroom with a four-track cassette recorder, laying down demos for dark, brooding songs about the hard-scrabble lives of the blue-collar folks he grew up with and stories of criminals like the killer Charles Starkweather, who inspired the title track, all infused with Southern Gothic literary references and reflections on his childhood. Unhappy with the attempt to record these songs with his band, Springsteen insisted on releasing the crude 4-track cassette demos with little to no fanfare.

The movie attempts to investigate these songs and that potentially disastrous career decision, but narrative cinema is a notoriously poor medium for exploring the inner workings of a creative mind. Great movie scenes of writers writing, or finding inspiration for their subjects, are very few and far between. (The only example that comes readily to my mind is in Amadeus, in what I assume is the utterly fictional moment when Mozart is listening to his mother-in-law berate him in her high, squaking voice which gives him the idea for arguably his most famous composition, the Queen of the Night aria in The Magic Flute). There are no such clever or fanciful depictions of this type of creative revelation in Cooper's movie. There are only the old stand-bys: writing words and internal thoughts on a page, watching the writer looking at places or things he will write about, and (worst of all) the invention of a fictional love interest to enable scenes of joy and conflict that could explain how and why things went down the way they did.

The thing is, this movie's fictional love interest, a pretty young single mom named Faye Romano (Odessa Young), doesn't provide this kind of exposition or insight. Springsteen's long-suffering manager and record producer, Jon Landau (Jeremy Strong), is already there to handle all those scenes. So the only function the Faye character serves is to provide the movie with its requisite pretty girl and to distract our protagonist from what is meant to be the lowest point of his life, thereby undercutting the movie's entire raison d'etre.

And let's talk a bit about those Jon Landau scenes. These are some of the most ungainly examples of a movie character forcefully declaring what should be subtext and themes I've ever seen. Scene after scene is a showcase for the type of goofy-voiced monologuing Strong has built his career on. Only this time, the performance is laughable. The previous year, Strong was Oscar-nominated for a similar role in The Apprentice, playing Donald Trump's mentor, the sinister shyster Roy Cohn, and was not only wildly entertaining in embodying such an extreme character, but also managed to make Cohn somewhat sympathetic (no small feat). But as Landau, Strong is little more than a goofy voice and a bug-eyed face, and when playing two-hander scenes with the perpetually wetted-down Jeremy Allen White doing his dubious Bruce Springsteen impression, these scenes play like SNL skits.

Even more hilarious than the scenes where Landau explains Bruce to Bruce are the scenes when Landau explains Bruce to other people, like a Columbia Records executive (David Krumholtz) who doesn't want to release Nebraska the way Bruce does, or the producer and mixing engineer Chuck Plotkin (Marc Maron), who can't deliver the sound Bruce wants, or Landau's wife (Grace Gummer), who I don't think utters a single word in the movie, she just sits there slackjawed listening to her husband explain Bruce to her (and to us). Strong would only need to up his performance one notch for these scenes with Landau and his wife to feel right out of Walk Hard.

Speaking of not uttering a single word, the famed E. Street Band is only glimpsed briefly on stage in this movie (there are almost no scenes of Bruce performing at one of his famous concerts) and in the recording of "Born in the USA." This choice feels like an attempt to avoid another terrible cliché of the musical biopic: having famous actors play famous people reenacting famous career milestones. But without the band having any voice or presence in this story, the viewer must bring prior knowledge of Springsteen's career to the movie. Otherwise, you think Nebraska was released when he was still a struggling wannabe rocker, not the chart-topper he was at the time. The movie almost needs its audience to understand its protagonist as a much simpler man than he obviously was. It doesn't want to explore how he used his music and stage performance to outrun his demons; rather, it follows the Rocketman formula of showing a wildly famous rock star when he was just starting out, before he's found his confidence, struggling to adapt to success. So we're shown scene after scene of Bruce saying, "No! This ain't right! This ain't the way I feel it!" and Lando saying, "Don't worry, Bruce. We'll get it. We always do." Seriously, that happens at least five times in this movie.

Oh, woe is the pain of the tortured artist who can't express himself in life nor exorcise the demons of his past, so he must pour all that pain into his art and push away everyone who loves him. Of course, many of the great works of art in our culture have indeed been created by people suffering from severe mental illness, depression, or suicidal tendencies. However, when making art about this truth, one must find a way to transcend cliché, avoid simplistic pop-psychology, and work hard to circumvent the easy Hollywood-style solutions that belittle the very real conditions one is attempting to explore. In cinema, one must also make this type of internal exploration visually compelling. If a movie like this doesn't feel authentic, it devolves into something so contrived it verges on self-parody.

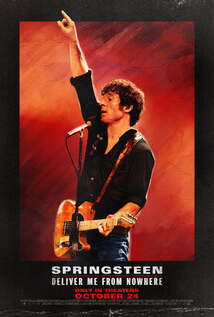

That's what we've got with Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere, a biopic that, while it avoids the dreaded cradle-to-the-grave biopic structure (or rather, cradle-to-successful-rehab-structure of most music industry biopics), checks most every other by-the-numbers box of this format. Actually, it doesn't really avoid the cradle-to-successful-rehab-structure; it just spends so little time on the final aspect of the process that if you blinked, you might miss it. But you sure as hell won't miss the fantasy parental apology scene. Good Lord, can this empty, artificial trend please DIE already?

Combining boomer biopic and millennial apology porn, the latest reductive music bio explores the artistic process behind an iconic album using cinematic's most uncreative forms of expression.