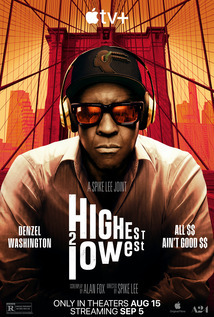

Spike Lee and Denzel Washington team up for the sixth time in this contemporary, New York-set remake of Akira Kurosawa's crime thriller High and Low. Washington plays music mogul David King, a power player who has reached the pinnacle of wealth and success, but has aged a bit past his prime as a tastemaker. The media conglomerate to which he sold his music label years ago is now hoping to sell off that company, which King spent his life building. King, however, thinks his ears still have some life left in them, and he plans to buy back the label himself when he learns that his son has been kidnapped and is being held for ransom. The police spring into action, but things shift dramatically when it's discovered that the kidnapper snatched the wrong kid and is not holding King's son but rather the son of King's driver and childhood buddy, Paul (Jeffrey Wright). But the kidnapper (rapper A$AP Rocky) doesn't change his ransom demand, and King is less willing to part with the majority of his net worth to rescue the son of his friend than when he thought his own child was taken. Thus, the brilliant themes of class, identity, and loyalty inherent in Ed McBain's 1959 novel King's Ransom, on which this is the fourth screen adaptation, are laid out.

The most famous version of McBain's story is unquestionably the Kurosawa picture, which is my favorite of the modern-day films by the legendary Japanese filmmaker. That movie is ingeniously structured into three acts, each of which feels like a different genre: a domestic drama chamber piece that evolves into a police procedural, and culminates in a film noir about a desperate man taking the law into his own hands. The film stars Kurosawa's favorite leading man, Toshirō Mifune, as wealthy shoe executive Kingo Gondo. It's fitting that Washington is to Lee's film what Mifune is to Kurosawa's, and changing the protagonist's business from a manufactured good like shoes to a commercial art form like music enables Lee and screenwriter Alan Fox to pepper the film with commentary about the state of how art is created, distributed, and consumed in today's world.

There are some other clever narrative, thematic, and production parallels between High and Low and Highest 2 Lowest, but unfortunately, visual storytelling isn't one of them. High and Low is a master class in widescreen cinema in which Kurosawa virtually reinvented how Cinemascope could be used, making his compositions all about the sides of the frame rather than the center. The critical theme of class hierarchy in Japanese society is visually expressed through Kurosawa's arrangement, costuming, and physical direction of each of the many characters occupying nearly every frame shot in Kingo Gondo's penthouse apartment during the first act. It is a thing to behold. I can understand Lee not wanting to even attempt something like it, but how about finding another interesting way to shoot a bunch of scenes with people sitting and talking in a penthouse? All Lee seems capable of is capturing his actors in many scenes with multiple cameras at different focal lengths, sliding back and forth on dollies, and then cutting randomly between these shots. Seriously Spike, that's some amateur-level coverage. It's the way directors shoot when they have to work around the performances of bad actors, but you've got Denzel Washington and Jeffrey Wright!!! If one of your NYU students turned in this weak-ass shit, would you praise it?

Editor Barry Alexander Brown has always been one of my heroes because of his work on Lee's early films. So, a question for him: Barry, what's up with the random cutting? Did you have ChatGPT make these edits? Is this first act so damn choppy because the film would have run too long if shots played out in a single take? That's another amateur move/excuse. The young Spike Lee never had a problem letting long scenes of dialogue play out in long takes with both subtle and elaborate camera moves. It is one of the reasons we remember the dialogue and the performances in movies like She's Gotta Have It, Do the Right Thing, and Malcome X so well. The older Spike seems to have lost confidence (in the audience probably more than in himself). The one time he lets a scene play out in a single take —a bedroom confrontation between King and his son, Trey (Aubrey Joseph), is the best scene of the whole first act. Damn shame the rest couldn't be as good.

Fortunately, the film recovers from its awkward, protracted start once Denzel gets out in the street. The sequence in which King, following the kidnapper's strict instructions, carries the king's ransom in a heavy backpack on a crowded subway to Yankee Stadium (where New York is playing Lee's hated Boston Red Sox, of course) during the Puerto Rican Day parade is as thrilling and cinematic as the sister sequence in High and Low in which Mifune tosses two briefcases full of money from a speeding passenger train. The whole episode is a nail-biter, and the 70-year-old Washington plays the hell out of it. He looks driven and dangerous, but the kidnapper's plan outfoxes King and the cops. The middle section is where this film shines, but several key set pieces in the final act also stand out. Too bad the narrative turning point into the third act is such a clumsy fumble. Even if the cops were painted as clueless or racist (which they aren't), there's no way they would reject the vital clue King discovers that will eventually lead him to being face-to-face with the kidnapper. It seems unfair that, in order to get the couple of major confrontation scenes this movie builds up to, we have to endure such hackneyed expository and transitional scenes.

I'm always longing for Spike Lee to make more movies that don't originate with him, working from other people's screenplays and collaborating with powerful creative producers outside his production company, because this type of effort often yields his best work, such as Malcolm X, Clockers, 25th Hour, and the endlessly entertaining Inside Man. But coming on to remake such a classic of cinema isn't exactly what I had in mind. Still, the Spike signatures, while all there, are toned down to a reasonable level in this movie (except for the orchestral score, which, as usual, is way too loud in the mix). Still, all Lee's stylistic tropes and motifs fit well in Highest 2 Lowest. The double dolly shots, where actors appear to float, are used in dream sequences, which prevent them from pulling us out of the narrative. The celebrity cameos that pop up are fitting for the setting and the main character's status. And the one-two punch of forthwall breaking and the dissing of Lee's least favorite Boston sports teams or players works incredibly well in the aforementioned train sequence—watching the film at one of Boston's largest cinemas played especially hilariously when a character on the train practically sticks his head out of the screen and yells, "Boston Sucks!" at the crowd. That moment does break the reality a bit, but it comes at such a tense point in the film that it serves as an effective moment of comic relief more than a distracting personal aside from the director.

The movie still feels personal, but its thematic content and subtextual commentary are more universal in nature. This is a movie about getting older, about contending with the new kids on the block and their new ways of creating art and doing business that seem alien or shallow to the older, master practitioners (or those of us who can only appreciate older master practitioners). It is also about not forgetting your roots, and how that becomes increasingly difficult with age and success. I'm not sure how I feel about the final scene in this movie in relation to these themes. It's uplifting to see King, the great arbiter of pop music, opening his mind to a possible voice of the future. I can't tell what's going on behind Denzel's eyes in the final shots. Is he truly excited about what he's hearing, or is he pragmatically yielding to others' tastes? That's one of the things that makes Washington such a great actor; it's not a blank expression he wears here, but it can be read a few ways. Lee's movies would benefit from more ambiguity like this.

There are many highs and lows in Spike Lee's uneven remake of the great Akira Kurosawa crime thriller; the performance of Denzel Washington as a wealthy music mogul whose son is kidnapped and ransomed is the biggest high.